Where to Invest $100,000 Right Now? Ask the Experts

Today, investors face a dilemma. Inflation is rising. Nearly every firm from Goldman to BlackRock project equity returns under 5% until 2035. The global pandemic has completely disrupted markets.

Finding promising investments is harder than ever.

Recently, Bloomberg asked financial experts where they’d invest $100,000 today. The response? They overwhelmingly recommended alternative assets, like art.

I recently took their advice, investing in multimillion-dollar art myself.

Here’s why:

- Contemporary art appreciated 14% annually on average from 1995-2020,

- Global art industry is expected to grow by 51% by 2026

- 0.01 correlation to public equities

Thankfully, I didn’t have to buy the entire painting to invest.

Instead, I used Masterworks.io—the tech unicorn that lets you invest in art like stocks in a company. They use AI to identify works by artists like Picasso, Banksy, and Basquiat—then securitize and issue shares of those paintings.

Actionable insights

If you only have a couple minutes to spare, here’s what investors, operators, and founders can learn from OpenSea.

- NFTs are for real. Whether cynic or supporter, the numbers show that non-fungible tokens are far from frivolous. So far this year, NFT sales have totaled more than $13 billion, with much of that sum arriving in the last two months.

- Running lean is vital for markets with high volatility. OpenSea maintained a small team for its first few years, with just 7 employees as of late 2020. That allowed the company to weather the crypto bear market, hanging in until NFTs took off.

- OpenSea is extremely dominant. The exchange boasts a market share of 97%. That’s thanks, in part, to OpenSea’s superior asset breadth, easy listing process, and robust filtering system.

- Decentralization doesn’t have to be doctrinal. Much of the crypto community seems to view decentralization as both a source of legitimacy and a cure-all. While there’s clearly room for decentralized players — Uniswap being one example in the token exchange space — centralized companies can also thrive. OpenSea is the latter.

- Investors may want to watch out for new types of NFTs. If you’re feeling irked you missed out on CryptoPunks, Bored Apes, and Art Blocks, there may be some consolation. New formats are constantly being created; two experts suggest music and “intelligent” NFTs are worth watching.

What are the most dominant companies in the world, by market share?

Chances are a few names come to mind: Google almost certainly, Facebook perhaps, Amazon, depending on the category.

Good answers, all of them. Google holds a 92% market share in search, Facebook and its associated properties boast more than 3x the active users as its next competitor, and Amazon’s domestic e-commerce dominance is pegged at 50%. (AWS’s share in cloud computing is 31%.)

Investors laud and governments squabble over this kind of eminence, this level of control. And yet, OpenSea bests all of them.

Since its founding in 2017, the NFT marketplace has grown to become the undisputed leader in the space with a share that exceeds 97%, and volume 12x that of its closest rival. The intuitive response to these figures is to ask about the market size. Sure, OpenSea is winning, but winning what, exactly?

Whatever one’s position is on the space, these numbers illustrate that NFTs are far more than a trifling interest and that OpenSea is more than just a peddler of esoterica. Already this year, more than $13 billion worth of NFTs have sold, with $25 billion in annual gross merchandise volume (GMV) within touching distance should sales for the rest of the year match last quarter. Such scale not only puts OpenSea ahead of its competition but beyond traditional, web2 marketplaces. In its most recent quarterly report, Etsy reported $3.04 billion in GMV; OpenSea surpassed that in August alone.

Coupled with the high-octane culture of the crypto space, such figures could contribute to a portrayal of OpenSea as a peddler of risk, the grandest bazaar in a kingdom of the unhinged. That would do a disservice to the creativity and cleverness of NFTs and misjudges what makes OpenSea unique.

This is not a company governed by a manic, YOLO-doctrine, but one guided by patience and conservatism. While adversaries experiment with new features and different models, OpenSea has obsessively focused on improving its core product. The result is a subtly paradoxical business, one that’s empowering something radical, but doing so with moderation — a reasonable revolutionary.

Today, we’ll brave the open seas ourselves, exploring the company’s past, present, and future. Read on for a voyage alighting on:

- Origins. WifiCoin and the pivot that led to OpenSea.

- Market. Revisiting NFTs and their development.

- Product. The subtle moats surrounding OpenSea.

- Leadership. Devin Finzer’s disciplined world-building.

- Valuation. A16z’s deal of the year.

- Competition. Rarible, Foundation, and others are coming for the king.

- Vulnerabilities. How OpenSea might flounder.

- Frontier. Where will NFTs go next and is OpenSea well-positioned?

Wagmi (to the end of this piece).

Origins: The Short Reign of Wificoin

Devin Finzer’s first hit business came in 2011. On Halloween of his junior year, the computer science student released his creation to the rest of Brown University’s student body.

Built with fellow students, Coursekick was a social class registration system that made it easy to pick your own classes and see what your friends were signing up for. Especially compared to the decrepit incumbent system, it proved a popular proposition. Within a few days, CourseKick had 500 users; a few days later it hit 1,000. Little more than a week later and 20% of Brown’s student body was on the platform.

In an interview with the school newspaper, Finzer described his vision to create “Pandora for classes.”

While that didn’t come to fruition, CourseKick served as valuable training for not one but two of the most successful founders in recent memory — one of Finzer’s co-founders was Dylan Field, CEO of design platform Figma, last valued at $10 billion. It’s surreal to visit Coursekick’s untended Twitter page and find the pair, ten years younger, celebrating their creation’s traction:

The experience at CourseKick stoked an entrepreneurial obsession for both men, though it would take Finzer longer to find a project in which his talents fully flourished. After graduating, he headed to Pinterest, working as an engineer on a growth team. Less than two years later, he had decided to build something of his own yet again.

In April of 2015, just a month after departing Pinterest, Finzer rolled out two new projects: Iris Labs and Claimdog. The first of those developed a suite of ophthalmological tools including a series of eye charts for the iPhone.

Though that seems to be have been a modest success — the apps are still in use, and Finzer’s LinkedIn states the suite has received 1.2 million downloads — Claimdog was the real focus.

It was an ingenious idea, well-articulated by Finzer in the company’s Product Hunt launch post:

Claimdog lets you search to see if a business owes you money. There is over $60 billion of “unclaimed property” or “missing money” in the United States, and our mission is to increase the awareness and transparency around this issue.

Unclaimed property is created when a business owes an individual or organization money, but wasn’t able to get it to them successfully. For example, say you forget to cash a check — where does that money go? State governments require that a business must, by law, turn it over to them after a period of time has passed. Uncashed checks, stock dividends, checks sent to old addresses, abandoned bank accounts or PayPal accounts, and inheritances are all common sources of these unclaimed property.

The numbers are staggering — there is over $60 billion owed.

Finzer ran the business for a little over the year before receiving an acquisition offer from CreditKarma, one that he and his co-founder accepted. Under its new ownership, Claimdog became the parent company’s “Unclaimed Money” product.

It was while working at his acquirer that Finzer fell down the crypto rabbit hole, becoming increasingly fascinated by the blockchain and the new economic system to which it was giving rise. That was a sharp juxtaposition from the more staid financial realm of his day job and coincided with the bull-run of late 2017.

By the fall of that year, he’d decided he wanted to build a business in the space, teaming up with another young software developer, Alex Atallah. A CS graduate from Stanford, Atallah’s experience neatly mirrored Finzer’s: he founded “Dormlink” in college, a social network for student quarters, before taking on the CTO-mantle for two further startups. Like Finzer, he’d developed an obsession with the crypto space that he wanted to take further.

In September of that year, Finzer and Atallah presented their project at Techcrunch’s Hackathon. Wificoin was in keeping with projects that had gained prominence in the space. In exchange for sharing access to a wifi router, users could earn coins, that could, in turn, be used to buy wifi access from others in the company’s network. In that respect, it was not dissimilar to Helium, a network sharing platform built on the blockchain that had raised an impressive Series B from Google Ventures, the year before.

Despite Atallah admitting that the product was “very hackable” in its current instantiation, the pair were accepted to Y Combinator to take their project further.

It was, by some accounts, an uneasy fit. Though rightfully known as a great talent and opportunity spotter, YC has not always shown a nuanced understanding of crypto. One former OpenSea employee expressed the belief that YC’s team was skeptical of the space in those days, while in our discussion, Finzer acknowledged teething problems.

“YC is certainly not tailored toward crypto companies,” he said, remarking that the accelerator relies on a template for startup building that feels alien in the world of web3. These novel businesses are “exceptions to the rule,” according to Finzer.

YC’s apprehension might have been influenced by Finzer and Atallah’s near-immediate pivot. In the interim between Wificoin’s acceptance to the program and its start in January of 2018, the crypto market had indelibly changed.

November 28, 2017 proved a historic day for the crypto community, though its significance came disguised — like so many other innovations — as a toy.

Though a test version had debuted at ETH Waterloo the month prior, that date represented the official launch of CryptoKitties. These goofy digital cats generated huge interest through the end of that year and into the next with frenzied bidding seeing one collectible, “Genesis,” selling for 247 ETH, roughly $118,000 at the time. (In case you’re wondering, that’s $894,000 based on this week’s prices.)

While some scorned the project (and many continue to), others saw past the googly-eyes. A CryptoKitty was not just a cute drawing, but a “non-fungible token” (NFT) built on top of a cryptographic standard called ERC-721, which supported other NFTs. Now, for non-crypto natives, this might sound like impenetrable jargon, but I promise it’s not as hard to understand as you might think, and is — I think — important.

Let’s quickly ask ourselves three questions:

- So, what is an NFT again? It’s a unit of data that cannot be changed. That unit can be anything: a picture, a song, a video, or even a drawing of a wacky cat.

- Why would someone want to buy one of these? That’s a longer conversation and one I’ve written about here, but it often has to do with status, scarcity, and belonging. Owning an NFT can grant clout, showcase your personality, or give you access to private groups.

- How does ERC-721 play into this? Think of it as the underlying infrastructure for projects like CryptoKitties. What’s important to know here is that ERC-721 is also the infrastructure for many projects beyond CryptoKitties. So if you could build a marketplace on top of ERC-721, you could easily support other NFTs.

It was this last point that really stuck out to Finzer.

What led us to think this could be much bigger [was that] there was a standard for digital items…Everything that came out after CryptoKitties would comply with that same standard.

He and Atallah decided to jettison their work on Wificoin and go all-in on building “a marketplace for the metaverse,” starting with CryptoKitties. Given the paucity of NFTs created at that time, that didn’t look like a particularly exciting proposition. But the pair valued the novelty of what they were doing:

When you’re starting a project you’re looking for something that hasn’t been done before. This hadn’t been done before.

History is full of moments of simultaneous invention. Think of Leibniz and Newton cooking up calculus, or Darwin and Wallace deciphering evolution, each revelation found independently. While not of the same magnitude, the potential for a marketplace built on ERC-721 looks like another example of multiple discovery.

Finzer and Atallah were not alone. At almost the exact same time as they made their pivot, another team had decided to build a solution in the space. And in many respects, they seemed like the better bet.

Composed of four ex-Zynga employees, Rare Bits seemed to have the talent to capitalize on this new space. After all, NFTs were going to be mostly used by gamers, right? The industry’s perspective at the time was that NFTs were likely to appeal to this segment— offering a game developers a way to sell new skins, special weapons, and other digital goods. Who better to build a marketplace for that than the team that had produced lobotomizing-megahit, Farmville?

On the same day in February, 2018, OpenSea and Rare Bits launched on Product Hunt.

OpenSea described itself as “Ebay for cryptogoods.”

Rare Bits used, “A zero fee Ebay-like marketplace for crypto assets.”

By the end of day, OpenSea had bested its rival, garnering 447 to Rare Bits’ 230. Both were crushed by a slew of others including Intel’s new smart glasses, a book on interviewing for UX jobs, and a set of “indestructible tights.”

The roles were reversed when it came to the venture markets. After graduating from Y Combinator, OpenSea succeeded in raising $2 million from a strong cast including 1confirmation, Founders Fund, Coinbase Ventures, and Blockchain Capital. Impressive work, but far behind the $6 million Rare Bits had secured a month earlier, with participation from Spark, First Round and Craft.

Richard Chen, a General Partner at 1confirmation summarized the consensus at the time, while explaining his firm’s bet:

Rare Bits was a much more polished team on paper – they were ex-Zynga and raised a lot more money than OpenSea from traditional VCs. However, the OpenSea team was more lean and scrappy. Devin and Alex did a great job living in Discords to discover new NFT projects and out hustled Rare Bits in getting these projects listed on OpenSea and attracting most of the trading volume on OpenSea instead of Rare Bits. At the time we invested in April 2018, OpenSea was already doing ~4x the volume of Rare Bits.

The distance between the two companies only seemed to widen over time, despite the fact that Rare Bits prided itself on taking no commissions on first sales (OpenSea took 1% in 2018), and refunding users for any gas fees incurred.

Such beneficence seemed out of synch with the “crypto winter” that had gripped 2018, however. While Rare Bits burned capital to maintain heat, OpenSea seemed to take an alternate approach, charging fees and running lean. As late as August of 2020, the company had just seven employees.

In a bid for volume, Rare Bits launched new experiments, including a partnership with Crunchyroll that allowed users to collect “digital stickers” of anime characters. Meanwhile, OpenSea stayed focus, relentlessly improving its core exchange, even as interest in the sector wanted. When asked why OpenSea had out-competed Rare Bits over the long run, Finzer responded:

[It was our] willingness to be in the space for the long haul, regardless of the immediate growth trajectory. We wanted to build a decentralized marketplace for NFTs, and we were fine for it to be small for 3-4 years.

By 2019, Rare Bits had seemingly closed shop. Today, if you visit the site, it redirects to CoinGecko, though no sale was ever announced.

For OpenSea, the story was just beginning.

Market: Welcome to the pfp party

It’s hard to grasp just how much the NFT market has grown in the span of a year.

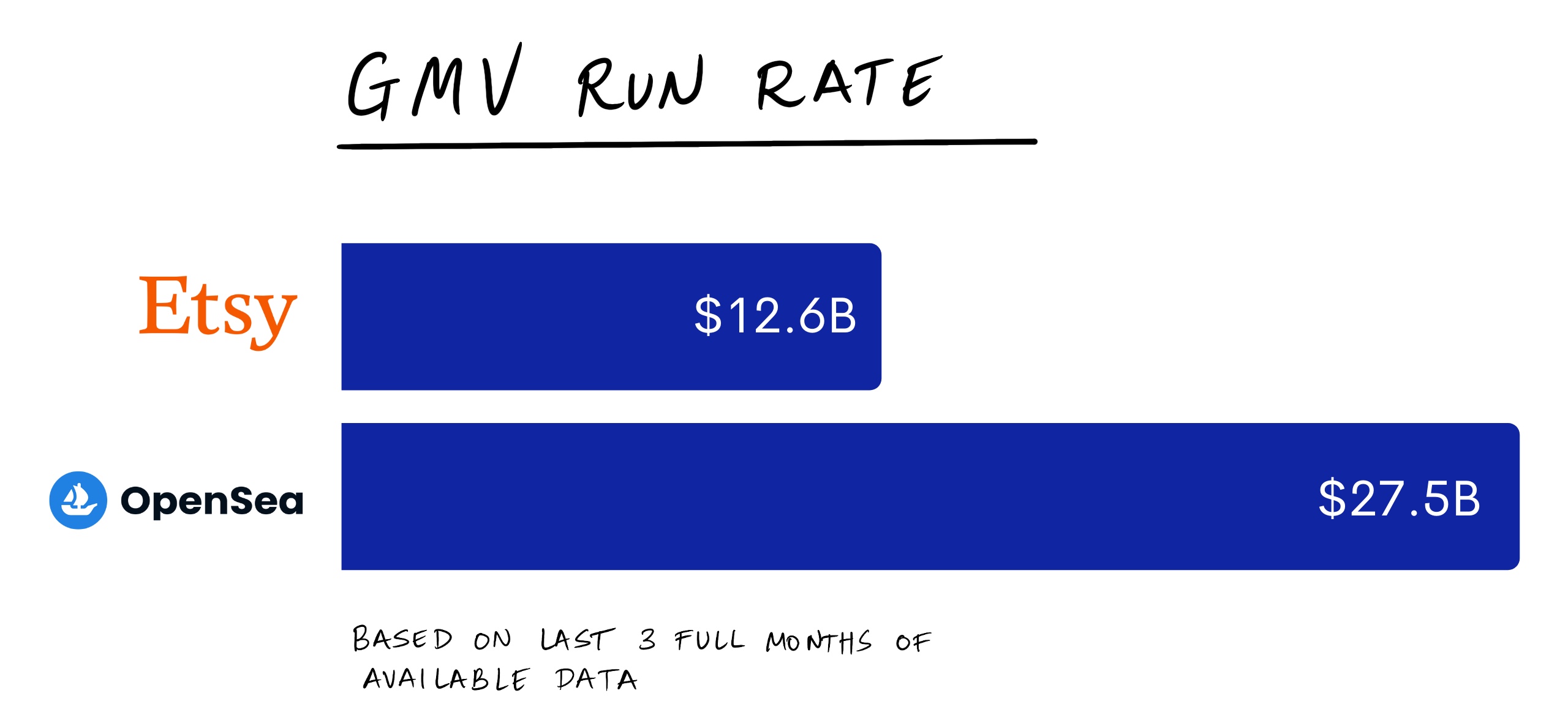

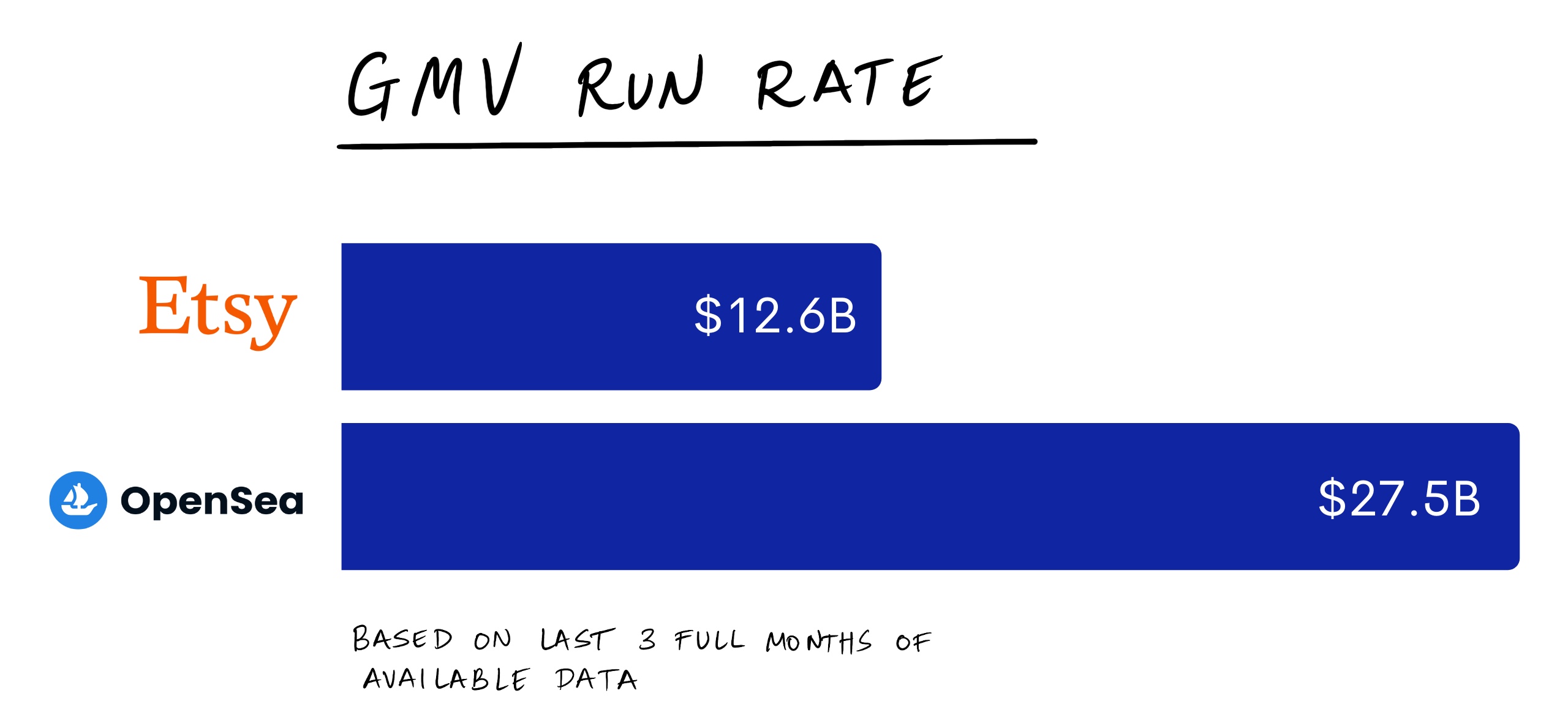

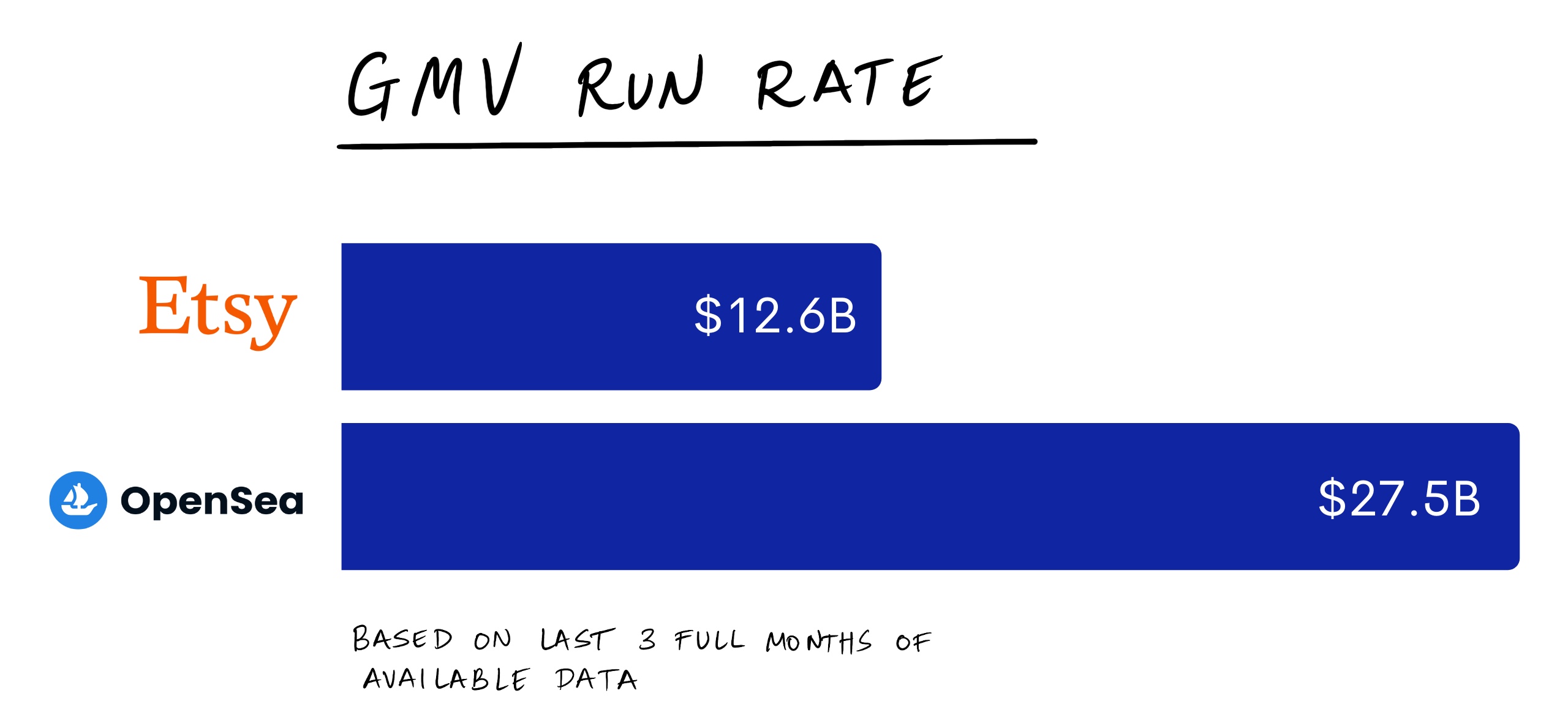

Earlier in this piece, we noted that OpenSea alone was on track to surpass $27.5 billion in volume for 2021. Should the company hold on to its 97% market share, that suggests a total annual GMV of $28.4 billion.

NFT sales in 2020 were $94.8 million. That’s a 30,000% increase year over year. Our brains are not made to comprehend this kind of growth, this sudden gigantism. In the blink of an eye, NFTs have matured from a nettlesome triviality to a strolling behemoth.

Much of that is down to the popularization of profile picture NFTs, known as “pfp” projects. The movement’s notable exponents include CryptoPunks, Bored Ape Yacht Club (BAYC), Pudgy Penguins, Meebits, and many, many others.

These characters have proliferated, spreading across your friends and followers on social media, driving further collecting, speculation, and investment. (The lines between the three are often so blurry as to be indistinguishable from each other.)

Even industry insiders have found themselves surprised by this emergence, partially because it represents a deviation from initial expectations. As Rare Bits’ story illustrates, NFTs were expected to dovetail with the gaming landscape. Projects like Gods Unchained and Decentraland, The Sandbox, and Animoca Brands’ vehicles were expected to drive the space forward.

By and large, this has not been the case, with one massive caveat: Axie Infinity, which is both a blockchain game and boasts the highest volume among NFT projects. Nevertheless, when looked at holistically, pfps appear to be the dominant form. Five of the top ten projects by all-time volume can be reasonably classified as pfp offerings. By volume, they reach $5.4 billion, or 37.3% of the total. If Axie is excluded and replaced with the 11th project by volume — Sandbox — pfp’s share of volume across these projects would reach 73%.

Even Finzer admits he did not see the current wave coming. “We did not predict the rise of Bored Ape Yacht Club, or these other collectible things.”

That’s slightly surprising in some respects. For one thing, OpenSea was early to recognize the potential in crypto avatars. In the early days of 2018, Finzer actually pulled in old friend Dylan Field to help him cook up Ethmoji.

Users could cook up profile pictures using composable elements like eyes, a mouth, and accessories.

In Finzer’s push for focus, Ethmoji got the short shrift. Though it didn’t receive much attention it does seem to still be active, and as late as 2019 — a year after it was founded — Atallah tweeted that new avatars were still being created.

Perhaps the other reason it’s surprising that Finzer didn’t expect the pfp revolution is that OpenSea looks tailor-made for the moment. That has much to do with the company’s deceptively powerful product.

Product: Subtle moats

At a high level, OpenSea’s product is a simple one: it’s a marketplace to buy and sell NFTs. But its success is due to subtler factors. In particular, the company’s dominance seems to have been aided by the ease of listing, breadth of assets on the platform, and robust filtering and cataloging system.

Permission listing

Launching an NFT on OpenSea, whether that be an image or song, takes just a few clicks. (Aside: I’m going to be experimenting with this and sharing the results next week.) It’s a matter of filling out information on the piece and uploading relevant data, whether that be an image or something else.

Alex Gedevani from crypto researcher Delphi Digital described this as one of the determining factors behind OpenSea’s dominance:

[OpenSea’s] emphasis on being a permissionless market for NFT minting, discovery, and trading [explains its market share accrual]. This enabled the long tail of creators to easily onboard given a low barrier to entry relative to other platforms. This approach is what scaled the supply sides of creators which attracted users and liquidity, both on primary and secondary markets. If Uniswap is the marketplace for any altcoin, then OpenSea is the marketplace for any NFT.

Though other marketplaces have since followed suit, making the act of listing a product simpler, OpenSea clearly led the way here. It’s helped bring a huge array of assets to the platform.

Asset breadth

OpenSea divides its selection into eight categories: art, music, domain names, virtual worlds, trading cards, collectibles, sports, and utility.

As we’ve discussed, “collectibles” have proven the most popular category, but the spread above illustrates just how diverse NFTs can be and what a wide range of products OpenSea offers. According to the company’s website, collections on the platform surpass 1 million, with more than 34 million individual NFTs available to purchase. Remarkably, even this figure may be outdated, given that it sits alongside a declaration that OpenSea has handled $4 billion volume; we know it has done much more.

According to Mason Nystrom, an analyst at crypto data platform Messari, this inclusive approach proved a pivotal competitive advantage, particularly with regard to competitor Rarible (we’ll discuss this in more detail later in this piece):

OpenSea aggregated and offered a breadth of different assets. So while Rarible gained early volume when it launched because of its liquidity mining, Rarible didn’t aggregate other non-Rarible assets (i.e. Punks, Axies, art). So OpenSea became the go-to market/liquidity for many of these early assets. OpenSea also passed through royalties from other platforms, provided a great indexer, and great UI for filtering assets, verified contracts, and a way for users to create NFTs.

Maria Shen, partner at Electric Capital, highlighted a key part of OpenSea’s platform liquidity, it’s large quantity of NFTs available to “Buy Now.”

Capturing the “buy now” mechanism is important because the more “buy now” NFTs you have the more liquid your markets [are]…Opensea has the most “buy now”.

By embracing all manner of assets, OpenSea has made itself the NFT ecosystem’s default — a perception and position that may be hard for rivals to dislodge.

The platform’s range comes at a cost though — for a wide selection to be desirable, strong search and filtering is a necessity.

Robust filtering

NFT projects vary widely both in their overall form and in the details that contribute to their value. Characteristics that are vital to note for one project may be irrelevant to another. OpenSea shines in capturing, cataloging, and allowing users to search this information.

To explain what we mean, let’s look at two popular pfp collections: CryptoPunks and Bored Ape Yacht Club.

Here’s what CryptoPunks look like — they’re pixelated faces with differing complexions, haircuts, and accessories. While the majority are human, there are some zombie, ape, and alien punks.

These distinctions matter because they serve as a direct indication of rarity. Punks with common features (an earring for example), are likely to receive a lower price than the much scarcer alien punk, outfitted with a cap, sunglasses, and pipe. Indeed, “CryptoPunk #7804” with those attributes last sold for 4,200 ETH or $15.1 million at the current price.

Being able to filter by these qualities matters a great deal to potential CryptoPunk purchasers, but they’re useless to someone that wants to secure one of the legions of Bored Apes:

To the simian connaisseur, salient aspects include fur color, whether or not the ape is eating pizza, and luminescent eyes. One of the most expensive BAYC purchases on OpenSea was the acquisition of “#3749,” an ape with golden fur, a captain’s hat, and red, laser eyes. It sold for 740 ETH or $2.7 million at current prices. (Interestingly it was bought by the official account of The Sandbox, the blockchain game we discussed earlier.)

OpenSea gives users the tools to filter and search projects by the delineations that matter most.

This might seem simple, but it makes a huge difference to buyers. Richard Chen articulated this position:

People under-appreciate how important search and discovery is for NFTs. Each NFT project (e.g. Meebits, Lost Poets) needs custom search filters by attributes, which has to be added manually by OpenSea on a project-by-project basis. This creates a huge defensible UX moat for OpenSea that’s hard for other platforms to replicate. For example, on Rarible I can’t even filter Meebits for skeletons that are wearing headphones; thus it doesn’t make sense to do my NFT shopping on one platform and then checkout on a different platform. By having a great NFT shopping user experience on OpenSea, users stay on the platform to do the actual NFT trade with OpenSea’s smart contract.

By treating each project as fundamentally unique, OpenSea has built a platform that truly caters to the buyer, simplifying the browsing experience so that it may capture the purchase.

In sum, OpenSea looks like an unusually crafty product that positioned itself perfectly to capture the effervescence of the last year. With a permissionless approach to creation, a huge number of assets on the platform, and a strong filtering system, it looks like a business encircled by subtle but significant moats.

Leadership and culture: Good winners

It is seemingly impossible to beguile Devin Finzer into gloating.

Despite serving as CEO of one of the most consequential unicorns in the world, despite his brainchild exerting a lordly dominance over its dominion, he is soft-spoken and mild-mannered.

When explicitly asked about OpenSea’s success, he often deflects, turning to all the problems the exchange has yet to solve, all the improvements to be made. When questioned about the platform’s grand vision, what the years ahead may bring, he demurs, stating that the focus is to “try to improve the core marketplace.” He is almost pathological in his humility; an exceedingly good winner.

He is also, according to varied accounts, extremely focused. One former employee referred to him as “one of the most focused founders in the entire crypto space.” Chen described his first impressions of Finzer:

[He seemed] very stoic and focused on the top long-term company priorities…[He] doesn’t get distracted by short-term prices/speculation in the crypto market.

In the face of competitive countermoves and market turbulence, OpenSea has retained its concentration admirably.

That’s been helped in no small part by co-founder Alex Atallah. Chen described OpenSea’s CTO as a “10x engineer,” with a particular gift for React.js. Atallah was also characterized as having his ear to the ground of the crypto ecosystem, “living in Discords,” an activity that contributes to a keen sense for users’ needs. Like Finzer, he is apparently relatively conservative, with both described as “more risk-averse than the average founder.” If there’s an obvious weakness in their leadership this is it. Chen acknowledged as much, saying:

[Finzer and Atallah] prefer to be well-positioned to ride the macro NFT market trend rather than doing new initiatives to push the space forward.

The company that they’ve built seems to reflect this low-key demeanor, by and large. In our conversation, Finzer noted that he prefers a “flat” management structure with ample opportunities for employees to take initiative, regardless of their stated role. In our conversation, he mentioned a “pod” structure in which small groups banded together to tackle different projects, with leadership of these sub-groups determined by the participants.

For now, the company remains remarkably small, with a team of just 45 people. As alluded to earlier, that’s a sharp increase from a year earlier, with Finzer stating OpenSea had 7 employees in August of 2020. If it gets its way, it will be larger soon, with 21 job openings posted on Lever.

Perhaps its only natural that when growth arrives so quickly, things can slip through the cracks. The one conspicuous blight on OpenSea’s reputation arrived in September of this year. Users analyzed the transaction history of Nate Chastain, then the company’s head of product, finding that he had engaged in front-running. In several instances, Chastain appeared to buy NFTs he knew would be featured on OpenSea’s homepage, using the increased visibility to sell them at a higher price.

Such a maneuver ran counter to OpenSea’s policies around “manipulative” trading practices. Finzer expressed his disappointment in the aftermath, Chastain resigned, and OpenSea instituted a policy that prohibits employees from “using confidential information to purchase or sell any NFTs, whether available on the OpenSea platform or not.” They are also not permitted to purchase NFTs being featured on the platform.

It’s hard to fault OpenSea too strenuously for the actions of a single employee. But for one class of competitors, at least, the Chastain episode exemplifies the need for alternatives. Many are coming for OpenSea’s spot.

Valuation: A16z gets a steal

Before we get to OpenSea’s competitors, we must first flesh out our understanding of OpenSea’s valuation. In some respects, doing so is an exercise in futility — this is a (rapidly) moving target capable of making analysis made today look silly by tomorrow.

We’ve seen that play out in the venture markets, to Andreessen Horowitz’s credit. In late July of this year, the firm led a $100 million Series B in OpenSea at a $1.5 billion valuation. At the time, OpenSea had processed less than $1 billion in volume for the year and was averaging $8.5 million a month in fees for the year.

That looks like an absurd steal now. In the two months after a16z’s investment was announced, OpenSea’s GMV more than sextupled to $6.4 billion, with fees moving in synch. Over August and September, Finzer and company averaged $220 million a month in fees.

So, what should OpenSea be valued at today?

Direct comparisons are tricky given the extent to which OpenSea is a league of its own. But we can get an idea by looking at a smattering of marketplaces, crypto exchanges, and betting platforms. While none are perfect independently — traditional marketplaces deal in physical goods that carry radically different costs, exchanges may rely on different revenue streams like “payment for order flow,” and NFTs are not quite the same as fantasy NFL — they provide a useful base for comparison.

The figure below shows companies’ valuations — either public or from their last round — divided by their “revenue run rate.” This was calculated by extending their last three full months of publicly available data.

One of these things is not like the other.

OpenSea has clearly outgrown its last valuation. Were it given the same 13x multiple as Etsy, it would be valued above $24 billion. It is, of course, growing much faster, and should have a much lower cost structure given Etsy has 1,400 employees to OpenSea’s 45.

(Conversely, OpenSea’s revenue is much less reliable, and could, feasibly drop by 90% or more should we see a full crypto winter set in.)

Revenue run rate per employee comes in at a hilarious $41 million; Ebay’s hovers around $800,000.

If OpenSea is raising another round — and every growth investor must certainly be knocking at their door — it seems more than possible that just three months after it announced a Series B, the company is worth greater than 10x more. Katie Haun, take a bow.

Competition: Watch the throne

Right now, OpenSea’s lead looks almost unassailable. And while its product and selection give it defensibility, it operates in an incipient, highly dynamic market. That leaves space for all manner of competitors, including centralized NFT marketplaces, decentralized marketplaces, vertical marketplaces, and cryptocurrency exchanges.

Centralized marketplaces

Arguably competition is weakest among other centralized NFT exchanges, at least for the time being. Competitors include Nifty Gateway (now owned by Gemini), Foundation, MakersPlace, and Zora. In some instances, these platforms differ from OpenSea in selection and aesthetic — Foundation, for example, is a beautifully minimalist platform that has appealed to more design-sensitive creators — but nevertheless overlap. Many are also on the newer side with both Foundation and Zora founded in 2020.

Can this cohort hang with OpenSea in the long term? It’s hard to envision OpenSea being unseated given the network effects implicit in this business, but the growth in the NFT market should mean there’s more than enough space for alternate destinations to thrive. That’s particularly true if they’re able to build up supply in certain categories and specialize feature sets.

It’s also likely that OpenSea’s success will encourage capital to flow into the space as investors recognize the size of the prize. That could give upstarts the firepower to fight for share, especially of the many new buyers that are likely to flood into the ecosystem in the years to come.

The more fundamental threat may come from decentralized players.

Decentralized marketplaces

In “Sushi and The Founding Murder,” we outlined two fundamental “laws” of crypto:

- The Law of Fluid Power. Crypto operates antithetically to extant power structures, seeing traditional hierarchies as unearned and illegitimate. This can relate to long-surviving institutions like the traditional financial system or newer companies like Coinbase. In both cases, power is perceived to have been captured by a central entity that seeks to codify and strengthen its grip. Crypto wants power to be perfectly fluid, accruing to contributors according to their value to the community. In this respect, it’s not only about decentralization — a perfect distribution of power is often not desirable — but relative merit within a decentralized structure.

- The Law of Fluid Wealth. Similarly, the crypto world is skeptical of rent-seeking entities. Organizations that do not provide continuous value and effort, earning under the same rules as every other participant, are often considered compromised. Crypto wants wealth to be fluid, rewarding sustained value creation. Radically, crypto considers users to be essential parts of the value creation rather than consumers of it.

As things stand, OpenSea is an entirely centralized entity with total control of its platform. It charges a 2.5% fee that the company receives. (In addition to this fee, users have to pay for “gas,” essentially a transaction fee to the network.) In other words, neither power and wealth are fluid.

Will that matter in the NFT space? Some certainly think so.

A number of decentralized players have emerged over the course of the last year, of which Rarible is the most established. It’s also an interesting case in that the project began as a centralized entity that raised $16 million in venture funding before it declared its intention to become a DAO. As part of that transition, Rarible issued a token in the summer of 2020. $RARI could be earned by using the project’s platform and also granted governance rights.

On the back of that launch, Rarible briefly became the number one NFT platform by volume, as wash trading — the practice of buying and selling assets to inflate volume and pricing — drove up $RARI’s rate. It didn’t last though, with OpenSea’s superior platform eventually winning users back, as described by Chen:

Rarible launched a token for the sake of launching a token and didn’t think deeply about token economics. As a result they heavily incentivized wash trading from people farming the token, and for a few months last summer Rarible was doing more volume than OpenSea. But once the inorganic demand dried up then it became super clear that OpenSea was a much better product.

While Rarible’s approach was not an unqualified success, neither was it a failure. Its RARI token boasts a fully-diluted market cap of $430 million, and it is OpenSea’s closest competitor by volume — not bad for a project founded less than two years ago.

More importantly, though, Rarible outlined a potential vector for attack for future decentralized players. As mentioned in the Sushi piece, that community’s “Shoyu” project is one such example, though it is still not live. Holders will hope that the effervescence of the broader Sushi ecosystem can drive volume. One kink? According to a source, just one engineer has been tasked with building Shoyu — beating OpenSea is quite a task for one person to shoulder.

Artion is another notable attempt. Founded by Andre Cronje, the creator of Yearn Finance, Artion seeks to address common complaints levied against OpenSea. It charges no platform fee and is built on the Fantom network rather than Ethereum, a decision that makes transactions faster and reduces gas fees.

Artion is the logical conclusion of A16z partner Chris Dixon’s crypto dictum, “your take rate is my opportunity.” By taking 0% fees, Artion offers a strong incentive to use its platform. In turn, it has open-sourced its code so that others may easily fork and build on top of it.

When asked why he would build a project with no potential for profit, Cronje responded “I like to start fires.” (*With that, Cronje tossed the phone into a river and walked away as a building in the background exploded into flames, Denzel style.*)

Will a fee cut be enough to compete with OpenSea? Opinions differ. Chen suggested OpenSea’s product would be difficult to replicate:

It’s very difficult for OpenSea to be forked and vampire attacked. That’s because 99% of the engineering work is off-chain (e.g. search and discovery, infrastructure) and thus can’t be forked.

Messari researcher Nystrom had a slightly different perspective, however, underlining the advantages decentralized platforms have:

[P]ermissionless protocols…will be more composable, community-driven, resistant to harmful regulation, attract better talent, and profitable. These qualities are why most decentralized protocols will outcompete centralized competitors over the long run.

Ultimately, the second part of Nystrom’s answer explains how OpenSea might thrive despite the presence of powerful decentralized rivals.

I think there’s a place for both centralized and decentralized marketplaces in the same way that Coinbase and Uniswap are both successful. OpenSea is here to stay and will offer great onboarding, UI, and useful features.

Vertical marketplaces

Though not a direct competitor, OpenSea may see vertical platforms siphon off its volume. To an extent this is happening already, with several of the largest NFT projects facilitating buying and selling on their own exchanges.

If you want to buy an Axie, for example, you don’t start by visiting OpenSea. Rather, you head over to Axie’s “in-house marketplace.” There, you’ll find an interface tailor-made for the product, with perfect filtering and search. That’s augmented by a project-specific wallet and transaction tracker.

A similar dynamic exists for LarvaLabs (creator of CryptoPunks), NBA Topshot, and Sorare — all of which process meaningful volume on their own platforms.

Ultimately, while OpenSea does an excellent job of adapting itself to serve different NFTs, projects that devote significant resources to building a specialized platform will be hard to keep pace with. Finzer’s company will hope it can grow increasingly robust, win through its selection, and continue to host the long-tail of publishers unable or unwilling to create a custom solution.

Cryptocurrency exchanges

In Part 3 of the FTX Trilogy, “The Everything Exchange,” we outlined how Sam Bankman-Fried’s business was positioning itself as the venue for all manner of buying and selling. That included NFTs.

They’re not the only traditional cryptocurrency exchange interested in the space. As we mentioned earlier, Gemini acquired Nifty Gateway, giving it a foothold, while Binance operates its own sub-platform.

Will any of these worry OpenSea? For now, no. But there are compelling reasons why an NFT marketplace appended to a crypto exchange makes sense. As NFTs have become more valuable, with some priced in the millions, their financial utility has increased. Not only do they now require secure custody, but they can be used as collateral. Rather than basing its margin only on the tokens in your account, for example, FTX could take into account your ownership of a $3 million Fidenza.

Rather than a threat, of course, this could be viewed as an opportunity for OpenSea. Partnerships with major exchanges could be mutually beneficial, with NFT holders accessing higher leverage and token traders getting a way to buy collectibles without having to move funds between wallets.

OpenSea gives the impression of a company that has never worried about competitors, unduly. Though it can expect more rivals to join the fray in the coming years, if it keeps executing, there should be room to grow. Greater concerns may come from elsewhere.

Vulnerabilities: Too slow, too fast

Despite its magnitude, OpenSea is still a startup with just a few dozen employees and a track record spanning a handful of years. Even though it has executed well and capitalized on crypto’s teeth-chattering market expansion, it has vulnerabilities. Some may be within its control, many are not.

In particular, OpenSea will need to ensure it reacts to customer feedback to improve the platform, acts progressively to reduce regulatory risk, and braces itself for adverse market conditions.

Respond to customer feedback

Despite serving as the crypto world’s default venue, OpenSea sometimes gives the impression of an unloved platform. Users complain about the company’s fees, the high gas prices incurred by using the Ethereum blockchain, and the lack of decentralizing features like a token.

To their credit, OpenSea operates a customer portal where users can propose improvements and vote on previous submissions. The list is long:

One of the most common requests is for OpenSea to add support for other blockchains, including Cardano, Tezos, Solana, and others. As it stands, the company supports Ethereum and Polygon — though much less used, the latter does have lower gas fees.

Supporting Solana should be high on the list. The project has broken out over the past year (explained well in Not Boring’s “Solana Summer”) and seemingly has room to run. Its low fees and fast transaction processing may make it a good fit for NFTs, with a range of chain-specific apes, cats, and chihuahuas emerging, and a marketplace, Solanart, serving as the aggregator.

One project, The Degenerate Ape Academy, has already processed more than 950,000 Solana on Solanart, equivalent to $149 million at the current price. On OpenSea roughly 1.9 ETH worth of Degenerate Apes appears to have been traded.

When asked what he considered his strengths to be in our discussion, Finzer responded: “I try as hard as I can not to have an ego about things and see things as they are.”

That seems to be true. As mentioned earlier, OpenSea’s CEO often refers to the platform’s shortcomings and is set on correcting them. He’ll want to ensure OpenSea does not miss out on future breakout projects like Degen Apes. The challenge will be adding more features, more networks while maintaining the core product’s performance.

Regulation

Are NFTs securities?

Should domestic regulatory bodies make an affirmative determination, OpenSea’s business would undoubtedly suffer. Securities and the markets selling them must comply with SEC rules, a burden that would require significant work from OpenSea and fundamentally change the NFT buying process.

So far, regulators have given little indication of how they see NFTs and whether they fulfill the four prongs of the “Howey Test,” which determines whether an asset is a security. To meet the bar, the following criteria must be met:

- Money (or a money equivalent) was invested

- It was invested into a “common enterprise”

- This investment carries a “reasonable expectation of profits”

- Such profits are derived from the efforts of others

A legal scholar is best equipped to determine whether NFTs meet the bar, but even an outsider will agree that a money equivalent is invested, often with the expectation of value increasing. These potential profits do seem to depend on others’ work. Whether NFT projects represent a “common enterprise” is an altogether thornier matter.

OpenSea should use this period of uncertainty to proactively work with regulators to help define the appropriate boundaries and ensure their platform leads the way when it comes to compliance. If they can manage this well, regulation may prove less of a susceptibility than a source of defensibility against smaller, less rigorous players. Nystrom from Messari mentioned this point, while adding that it might curtail OpenSea’s selection:

As NFTs grow, OpenSea might end up relying on building a regulatory moat (similar to Coinbase) as opposed to offering riskier assets.

Gina Moon, the company’s General Counsel, may prove especially important here. Prior to joining OpenSea, she served on Facebook’s regulatory team. Finzer will need to make sure she has the latitude and support to take a proactive stance here.

Market meltdown

Though we’re believers in the creative and societal power of NFTs, it’s nevertheless true that the space is a sort of mania. Fraud, wash trading, and speculation are rampant, and prices do not always seem rational.

In the short term, that cocktail could cause buyers to sour, reducing OpenSea’s volume in turn. In all likelihood, that would be propelled by a broader shift away from cryptocurrencies — the current bull market surely cannot last forever — with investors moving away from the more fanciful edges of this universe, toward established projects. This might actually have a positive effect on the blue-chip NFT projects — crypto investors may see a CryptoPunk or Fidenza as a reasonably safe store of value. But at the very least, smaller projects, and the many supporting them, could see paper “returns” wiped out.

How will OpenSea cope with this kind of a downturn?

Like few other high-growth startups, OpenSea actually feels built to weather these kinds of events. As we mentioned, the company has operated with a lean, low-burn team for much of its life and has thrived by maintaining focus. Assuming it doesn’t suddenly develop a penchant for profligacy, it should have coffers to make it through a winter. It can productively use the period by picking off interesting vertical players, and readying itself for the next crypto rollercoaster.

Frontier: Where next for OpenSea and NFTs?

What will NFTs become?

This is the kind of question that can drive a fantasist wild. Already, the form includes pictorial art, music, fashion, games, domains, and countless other overlaps and imbrications between these forms. Just as vitally, the terrain is changing every day as new projects riff on established boundaries.

Loot, released by Vine founder Dom Hofmann in late August of this year, is an example of just how radically new trends can capture the imagination. As we’ve noted, much of NFT mania has been dominated by avatars — Loot zagged in the other direction, eschewing imagery for a black and white list of objects. The idea is that creators can build on top of Loot, giving the holders of this digital itinerary different venues to express and manifest their ownership.

Musical NFTs may be worth keeping an eye on, according to Chen:

Audio NFTs have surprisingly not taken off yet. A big reason is because NFT metadata right now mostly serves only images or videos. OpenSea is working on supporting important metadata for rendering audio files, which will be beneficial for projects like Catalog that’s building the platform for curated 1-of-1 NFT music.

Looking further ahead, “intelligent” NFTs could represent another frontier. Nystom outlined this opportunity:

We can expect the evolution of NFTs from merely static to dynamic aka “intelligent” NFTs with AI integrations and other cool features that evolve based on NFT usage.

This is heady stuff, with the only true boundaries being legal and technical. We may, someday in the future, buy avatars with “real” personalities, with thoughts that change and adapt.

If NFTs are already on track to do tens of billions in volume right now, what might a mature market manage?

OpenSea’s challenge is to successfully catalogue such a dizzying array of objects, growing in complexity. The opportunity is to capture as much of that growing volume as possible.

Doing so may require new products and features. Over the past couple of weeks, OpenSea rolled out a mobile app. Though it doesn’t allow buying and selling yet, it’s the first step towards a true multi-platform offering that could further popularize NFTs.

If we want to get a sense for where else the company might go, revisiting Coinbase’s roadmap might be a good call. In many respects, that seems to be OpenSea’s closest analogue — a centralized crypto exchange that serves as the natural on-ramp to the ecosystem, and is keen to play by the rules.

To wit, we should expect OpenSea to offer a institution-friendly product, not unlike Coinbase Pro. That could handle custody, high-priced purchases, and provide white-glove service.

If regulatorily possible, fractional ownership of NFTs would represent a massive unlock for the industry. As things stand, many are excluded simply by virtue of pricing. For example, the current “floor price” for a Bored Ape is 38.7 ETH, roughly $140,000. That’s beyond all but the affluent.

At the same time, holders of these NFTs have few options when it comes to locking in their gains. If you were fortunate enough to buy a CryptoPunk at $10,000 and have seen it increase to $1 million value, should you sell? What if the next week a similar piece goes for $10 million?

Right now, both buying and selling are all or nothing. Fractionalization would allow newcomers to buy into their favorite assets with less money — buying “shares” in a CryptoPunk, for example — while holders could take some winnings off the table while retaining upside.

Whether this becomes possible any time soon likely doesn’t matter for OpenSea too much. This is a market that seems to just be beginning.

Transcendentalist Ralph Waldo Emerson once said that “A great man is always willing to be little.”

Perhaps the same can be said of great companies. To remain humble in triumph, to see success not as the end-state but the beginning — these are qualities of generational businesses.

OpenSea appears to have this quality in its bones.

In Devin Finzer, the firm has a humble but deeply capable builder at the helm, supported by a CTO with the talent and disposition to scale with the company. Despite its formidable traction, OpenSea gives the impression of a business focused on its weaknesses, and committed to addressing them.

Revolution and moderation rarely sit well together, but OpenSea is the exception. We can be glad that as the web3 movement grows, a critical player executes not with ego or bombast, but a sense of reason.

Where to Invest $100,000 Right Now? Ask the Experts

Today, investors face a dilemma. Inflation is rising. Nearly every firm from Goldman to BlackRock project equity returns under 5% until 2035. The global pandemic has completely disrupted markets.

Finding promising investments is harder than ever.

Recently, Bloomberg asked financial experts where they’d invest $100,000 today. The response? They overwhelmingly recommended alternative assets, like art.

I recently took their advice, investing in multimillion-dollar art myself.

Here’s why:

- Contemporary art appreciated 14% annually on average from 1995-2020,

- Global art industry is expected to grow by 51% by 2026

- 0.01 correlation to public equities

Thankfully, I didn’t have to buy the entire painting to invest.

Instead, I used Masterworks.io—the tech unicorn that lets you invest in art like stocks in a company. They use AI to identify works by artists like Picasso, Banksy, and Basquiat—then securitize and issue shares of those paintings.

Actionable insights

If you only have a couple minutes to spare, here’s what investors, operators, and founders can learn from OpenSea.

- NFTs are for real. Whether cynic or supporter, the numbers show that non-fungible tokens are far from frivolous. So far this year, NFT sales have totaled more than $13 billion, with much of that sum arriving in the last two months.

- Running lean is vital for markets with high volatility. OpenSea maintained a small team for its first few years, with just 7 employees as of late 2020. That allowed the company to weather the crypto bear market, hanging in until NFTs took off.

- OpenSea is extremely dominant. The exchange boasts a market share of 97%. That’s thanks, in part, to OpenSea’s superior asset breadth, easy listing process, and robust filtering system.

- Decentralization doesn’t have to be doctrinal. Much of the crypto community seems to view decentralization as both a source of legitimacy and a cure-all. While there’s clearly room for decentralized players — Uniswap being one example in the token exchange space — centralized companies can also thrive. OpenSea is the latter.

- Investors may want to watch out for new types of NFTs. If you’re feeling irked you missed out on CryptoPunks, Bored Apes, and Art Blocks, there may be some consolation. New formats are constantly being created; two experts suggest music and “intelligent” NFTs are worth watching.

What are the most dominant companies in the world, by market share?

Chances are a few names come to mind: Google almost certainly, Facebook perhaps, Amazon, depending on the category.

Good answers, all of them. Google holds a 92% market share in search, Facebook and its associated properties boast more than 3x the active users as its next competitor, and Amazon’s domestic e-commerce dominance is pegged at 50%. (AWS’s share in cloud computing is 31%.)

Investors laud and governments squabble over this kind of eminence, this level of control. And yet, OpenSea bests all of them.

Since its founding in 2017, the NFT marketplace has grown to become the undisputed leader in the space with a share that exceeds 97%, and volume 12x that of its closest rival. The intuitive response to these figures is to ask about the market size. Sure, OpenSea is winning, but winning what, exactly?

Whatever one’s position is on the space, these numbers illustrate that NFTs are far more than a trifling interest and that OpenSea is more than just a peddler of esoterica. Already this year, more than $13 billion worth of NFTs have sold, with $25 billion in annual gross merchandise volume (GMV) within touching distance should sales for the rest of the year match last quarter. Such scale not only puts OpenSea ahead of its competition but beyond traditional, web2 marketplaces. In its most recent quarterly report, Etsy reported $3.04 billion in GMV; OpenSea surpassed that in August alone.

Coupled with the high-octane culture of the crypto space, such figures could contribute to a portrayal of OpenSea as a peddler of risk, the grandest bazaar in a kingdom of the unhinged. That would do a disservice to the creativity and cleverness of NFTs and misjudges what makes OpenSea unique.

This is not a company governed by a manic, YOLO-doctrine, but one guided by patience and conservatism. While adversaries experiment with new features and different models, OpenSea has obsessively focused on improving its core product. The result is a subtly paradoxical business, one that’s empowering something radical, but doing so with moderation — a reasonable revolutionary.

Today, we’ll brave the open seas ourselves, exploring the company’s past, present, and future. Read on for a voyage alighting on:

- Origins. WifiCoin and the pivot that led to OpenSea.

- Market. Revisiting NFTs and their development.

- Product. The subtle moats surrounding OpenSea.

- Leadership. Devin Finzer’s disciplined world-building.

- Valuation. A16z’s deal of the year.

- Competition. Rarible, Foundation, and others are coming for the king.

- Vulnerabilities. How OpenSea might flounder.

- Frontier. Where will NFTs go next and is OpenSea well-positioned?

Wagmi (to the end of this piece).

Origins: The Short Reign of Wificoin

Devin Finzer’s first hit business came in 2011. On Halloween of his junior year, the computer science student released his creation to the rest of Brown University’s student body.

Built with fellow students, Coursekick was a social class registration system that made it easy to pick your own classes and see what your friends were signing up for. Especially compared to the decrepit incumbent system, it proved a popular proposition. Within a few days, CourseKick had 500 users; a few days later it hit 1,000. Little more than a week later and 20% of Brown’s student body was on the platform.

In an interview with the school newspaper, Finzer described his vision to create “Pandora for classes.”

While that didn’t come to fruition, CourseKick served as valuable training for not one but two of the most successful founders in recent memory — one of Finzer’s co-founders was Dylan Field, CEO of design platform Figma, last valued at $10 billion. It’s surreal to visit Coursekick’s untended Twitter page and find the pair, ten years younger, celebrating their creation’s traction:

The experience at CourseKick stoked an entrepreneurial obsession for both men, though it would take Finzer longer to find a project in which his talents fully flourished. After graduating, he headed to Pinterest, working as an engineer on a growth team. Less than two years later, he had decided to build something of his own yet again.

In April of 2015, just a month after departing Pinterest, Finzer rolled out two new projects: Iris Labs and Claimdog. The first of those developed a suite of ophthalmological tools including a series of eye charts for the iPhone.

Though that seems to be have been a modest success — the apps are still in use, and Finzer’s LinkedIn states the suite has received 1.2 million downloads — Claimdog was the real focus.

It was an ingenious idea, well-articulated by Finzer in the company’s Product Hunt launch post:

Claimdog lets you search to see if a business owes you money. There is over $60 billion of “unclaimed property” or “missing money” in the United States, and our mission is to increase the awareness and transparency around this issue.

Unclaimed property is created when a business owes an individual or organization money, but wasn’t able to get it to them successfully. For example, say you forget to cash a check — where does that money go? State governments require that a business must, by law, turn it over to them after a period of time has passed. Uncashed checks, stock dividends, checks sent to old addresses, abandoned bank accounts or PayPal accounts, and inheritances are all common sources of these unclaimed property.

The numbers are staggering — there is over $60 billion owed.

Finzer ran the business for a little over the year before receiving an acquisition offer from CreditKarma, one that he and his co-founder accepted. Under its new ownership, Claimdog became the parent company’s “Unclaimed Money” product.

It was while working at his acquirer that Finzer fell down the crypto rabbit hole, becoming increasingly fascinated by the blockchain and the new economic system to which it was giving rise. That was a sharp juxtaposition from the more staid financial realm of his day job and coincided with the bull-run of late 2017.

By the fall of that year, he’d decided he wanted to build a business in the space, teaming up with another young software developer, Alex Atallah. A CS graduate from Stanford, Atallah’s experience neatly mirrored Finzer’s: he founded “Dormlink” in college, a social network for student quarters, before taking on the CTO-mantle for two further startups. Like Finzer, he’d developed an obsession with the crypto space that he wanted to take further.

In September of that year, Finzer and Atallah presented their project at Techcrunch’s Hackathon. Wificoin was in keeping with projects that had gained prominence in the space. In exchange for sharing access to a wifi router, users could earn coins, that could, in turn, be used to buy wifi access from others in the company’s network. In that respect, it was not dissimilar to Helium, a network sharing platform built on the blockchain that had raised an impressive Series B from Google Ventures, the year before.

Despite Atallah admitting that the product was “very hackable” in its current instantiation, the pair were accepted to Y Combinator to take their project further.

It was, by some accounts, an uneasy fit. Though rightfully known as a great talent and opportunity spotter, YC has not always shown a nuanced understanding of crypto. One former OpenSea employee expressed the belief that YC’s team was skeptical of the space in those days, while in our discussion, Finzer acknowledged teething problems.

“YC is certainly not tailored toward crypto companies,” he said, remarking that the accelerator relies on a template for startup building that feels alien in the world of web3. These novel businesses are “exceptions to the rule,” according to Finzer.

YC’s apprehension might have been influenced by Finzer and Atallah’s near-immediate pivot. In the interim between Wificoin’s acceptance to the program and its start in January of 2018, the crypto market had indelibly changed.

November 28, 2017 proved a historic day for the crypto community, though its significance came disguised — like so many other innovations — as a toy.

Though a test version had debuted at ETH Waterloo the month prior, that date represented the official launch of CryptoKitties. These goofy digital cats generated huge interest through the end of that year and into the next with frenzied bidding seeing one collectible, “Genesis,” selling for 247 ETH, roughly $118,000 at the time. (In case you’re wondering, that’s $894,000 based on this week’s prices.)

While some scorned the project (and many continue to), others saw past the googly-eyes. A CryptoKitty was not just a cute drawing, but a “non-fungible token” (NFT) built on top of a cryptographic standard called ERC-721, which supported other NFTs. Now, for non-crypto natives, this might sound like impenetrable jargon, but I promise it’s not as hard to understand as you might think, and is — I think — important.

Let’s quickly ask ourselves three questions:

- So, what is an NFT again? It’s a unit of data that cannot be changed. That unit can be anything: a picture, a song, a video, or even a drawing of a wacky cat.

- Why would someone want to buy one of these? That’s a longer conversation and one I’ve written about here, but it often has to do with status, scarcity, and belonging. Owning an NFT can grant clout, showcase your personality, or give you access to private groups.

- How does ERC-721 play into this? Think of it as the underlying infrastructure for projects like CryptoKitties. What’s important to know here is that ERC-721 is also the infrastructure for many projects beyond CryptoKitties. So if you could build a marketplace on top of ERC-721, you could easily support other NFTs.

It was this last point that really stuck out to Finzer.

What led us to think this could be much bigger [was that] there was a standard for digital items…Everything that came out after CryptoKitties would comply with that same standard.

He and Atallah decided to jettison their work on Wificoin and go all-in on building “a marketplace for the metaverse,” starting with CryptoKitties. Given the paucity of NFTs created at that time, that didn’t look like a particularly exciting proposition. But the pair valued the novelty of what they were doing:

When you’re starting a project you’re looking for something that hasn’t been done before. This hadn’t been done before.

History is full of moments of simultaneous invention. Think of Leibniz and Newton cooking up calculus, or Darwin and Wallace deciphering evolution, each revelation found independently. While not of the same magnitude, the potential for a marketplace built on ERC-721 looks like another example of multiple discovery.

Finzer and Atallah were not alone. At almost the exact same time as they made their pivot, another team had decided to build a solution in the space. And in many respects, they seemed like the better bet.

Composed of four ex-Zynga employees, Rare Bits seemed to have the talent to capitalize on this new space. After all, NFTs were going to be mostly used by gamers, right? The industry’s perspective at the time was that NFTs were likely to appeal to this segment— offering a game developers a way to sell new skins, special weapons, and other digital goods. Who better to build a marketplace for that than the team that had produced lobotomizing-megahit, Farmville?

On the same day in February, 2018, OpenSea and Rare Bits launched on Product Hunt.

OpenSea described itself as “Ebay for cryptogoods.”

Rare Bits used, “A zero fee Ebay-like marketplace for crypto assets.”

By the end of day, OpenSea had bested its rival, garnering 447 to Rare Bits’ 230. Both were crushed by a slew of others including Intel’s new smart glasses, a book on interviewing for UX jobs, and a set of “indestructible tights.”

The roles were reversed when it came to the venture markets. After graduating from Y Combinator, OpenSea succeeded in raising $2 million from a strong cast including 1confirmation, Founders Fund, Coinbase Ventures, and Blockchain Capital. Impressive work, but far behind the $6 million Rare Bits had secured a month earlier, with participation from Spark, First Round and Craft.

Richard Chen, a General Partner at 1confirmation summarized the consensus at the time, while explaining his firm’s bet:

Rare Bits was a much more polished team on paper – they were ex-Zynga and raised a lot more money than OpenSea from traditional VCs. However, the OpenSea team was more lean and scrappy. Devin and Alex did a great job living in Discords to discover new NFT projects and out hustled Rare Bits in getting these projects listed on OpenSea and attracting most of the trading volume on OpenSea instead of Rare Bits. At the time we invested in April 2018, OpenSea was already doing ~4x the volume of Rare Bits.

The distance between the two companies only seemed to widen over time, despite the fact that Rare Bits prided itself on taking no commissions on first sales (OpenSea took 1% in 2018), and refunding users for any gas fees incurred.

Such beneficence seemed out of synch with the “crypto winter” that had gripped 2018, however. While Rare Bits burned capital to maintain heat, OpenSea seemed to take an alternate approach, charging fees and running lean. As late as August of 2020, the company had just seven employees.

In a bid for volume, Rare Bits launched new experiments, including a partnership with Crunchyroll that allowed users to collect “digital stickers” of anime characters. Meanwhile, OpenSea stayed focus, relentlessly improving its core exchange, even as interest in the sector wanted. When asked why OpenSea had out-competed Rare Bits over the long run, Finzer responded:

[It was our] willingness to be in the space for the long haul, regardless of the immediate growth trajectory. We wanted to build a decentralized marketplace for NFTs, and we were fine for it to be small for 3-4 years.

By 2019, Rare Bits had seemingly closed shop. Today, if you visit the site, it redirects to CoinGecko, though no sale was ever announced.

For OpenSea, the story was just beginning.

Market: Welcome to the pfp party

It’s hard to grasp just how much the NFT market has grown in the span of a year.

Earlier in this piece, we noted that OpenSea alone was on track to surpass $27.5 billion in volume for 2021. Should the company hold on to its 97% market share, that suggests a total annual GMV of $28.4 billion.

NFT sales in 2020 were $94.8 million. That’s a 30,000% increase year over year. Our brains are not made to comprehend this kind of growth, this sudden gigantism. In the blink of an eye, NFTs have matured from a nettlesome triviality to a strolling behemoth.

Much of that is down to the popularization of profile picture NFTs, known as “pfp” projects. The movement’s notable exponents include CryptoPunks, Bored Ape Yacht Club (BAYC), Pudgy Penguins, Meebits, and many, many others.

These characters have proliferated, spreading across your friends and followers on social media, driving further collecting, speculation, and investment. (The lines between the three are often so blurry as to be indistinguishable from each other.)

Even industry insiders have found themselves surprised by this emergence, partially because it represents a deviation from initial expectations. As Rare Bits’ story illustrates, NFTs were expected to dovetail with the gaming landscape. Projects like Gods Unchained and Decentraland, The Sandbox, and Animoca Brands’ vehicles were expected to drive the space forward.

By and large, this has not been the case, with one massive caveat: Axie Infinity, which is both a blockchain game and boasts the highest volume among NFT projects. Nevertheless, when looked at holistically, pfps appear to be the dominant form. Five of the top ten projects by all-time volume can be reasonably classified as pfp offerings. By volume, they reach $5.4 billion, or 37.3% of the total. If Axie is excluded and replaced with the 11th project by volume — Sandbox — pfp’s share of volume across these projects would reach 73%.

Even Finzer admits he did not see the current wave coming. “We did not predict the rise of Bored Ape Yacht Club, or these other collectible things.”

That’s slightly surprising in some respects. For one thing, OpenSea was early to recognize the potential in crypto avatars. In the early days of 2018, Finzer actually pulled in old friend Dylan Field to help him cook up Ethmoji.

Users could cook up profile pictures using composable elements like eyes, a mouth, and accessories.

In Finzer’s push for focus, Ethmoji got the short shrift. Though it didn’t receive much attention it does seem to still be active, and as late as 2019 — a year after it was founded — Atallah tweeted that new avatars were still being created.

Perhaps the other reason it’s surprising that Finzer didn’t expect the pfp revolution is that OpenSea looks tailor-made for the moment. That has much to do with the company’s deceptively powerful product.

Product: Subtle moats

At a high level, OpenSea’s product is a simple one: it’s a marketplace to buy and sell NFTs. But its success is due to subtler factors. In particular, the company’s dominance seems to have been aided by the ease of listing, breadth of assets on the platform, and robust filtering and cataloging system.

Permission listing

Launching an NFT on OpenSea, whether that be an image or song, takes just a few clicks. (Aside: I’m going to be experimenting with this and sharing the results next week.) It’s a matter of filling out information on the piece and uploading relevant data, whether that be an image or something else.

Alex Gedevani from crypto researcher Delphi Digital described this as one of the determining factors behind OpenSea’s dominance:

[OpenSea’s] emphasis on being a permissionless market for NFT minting, discovery, and trading [explains its market share accrual]. This enabled the long tail of creators to easily onboard given a low barrier to entry relative to other platforms. This approach is what scaled the supply sides of creators which attracted users and liquidity, both on primary and secondary markets. If Uniswap is the marketplace for any altcoin, then OpenSea is the marketplace for any NFT.

Though other marketplaces have since followed suit, making the act of listing a product simpler, OpenSea clearly led the way here. It’s helped bring a huge array of assets to the platform.

Asset breadth

OpenSea divides its selection into eight categories: art, music, domain names, virtual worlds, trading cards, collectibles, sports, and utility.

As we’ve discussed, “collectibles” have proven the most popular category, but the spread above illustrates just how diverse NFTs can be and what a wide range of products OpenSea offers. According to the company’s website, collections on the platform surpass 1 million, with more than 34 million individual NFTs available to purchase. Remarkably, even this figure may be outdated, given that it sits alongside a declaration that OpenSea has handled $4 billion volume; we know it has done much more.

According to Mason Nystrom, an analyst at crypto data platform Messari, this inclusive approach proved a pivotal competitive advantage, particularly with regard to competitor Rarible (we’ll discuss this in more detail later in this piece):

OpenSea aggregated and offered a breadth of different assets. So while Rarible gained early volume when it launched because of its liquidity mining, Rarible didn’t aggregate other non-Rarible assets (i.e. Punks, Axies, art). So OpenSea became the go-to market/liquidity for many of these early assets. OpenSea also passed through royalties from other platforms, provided a great indexer, and great UI for filtering assets, verified contracts, and a way for users to create NFTs.

Maria Shen, partner at Electric Capital, highlighted a key part of OpenSea’s platform liquidity, it’s large quantity of NFTs available to “Buy Now.”

Capturing the “buy now” mechanism is important because the more “buy now” NFTs you have the more liquid your markets [are]…Opensea has the most “buy now”.

By embracing all manner of assets, OpenSea has made itself the NFT ecosystem’s default — a perception and position that may be hard for rivals to dislodge.

The platform’s range comes at a cost though — for a wide selection to be desirable, strong search and filtering is a necessity.

Robust filtering

NFT projects vary widely both in their overall form and in the details that contribute to their value. Characteristics that are vital to note for one project may be irrelevant to another. OpenSea shines in capturing, cataloging, and allowing users to search this information.

To explain what we mean, let’s look at two popular pfp collections: CryptoPunks and Bored Ape Yacht Club.

Here’s what CryptoPunks look like — they’re pixelated faces with differing complexions, haircuts, and accessories. While the majority are human, there are some zombie, ape, and alien punks.

These distinctions matter because they serve as a direct indication of rarity. Punks with common features (an earring for example), are likely to receive a lower price than the much scarcer alien punk, outfitted with a cap, sunglasses, and pipe. Indeed, “CryptoPunk #7804” with those attributes last sold for 4,200 ETH or $15.1 million at the current price.

Being able to filter by these qualities matters a great deal to potential CryptoPunk purchasers, but they’re useless to someone that wants to secure one of the legions of Bored Apes:

To the simian connaisseur, salient aspects include fur color, whether or not the ape is eating pizza, and luminescent eyes. One of the most expensive BAYC purchases on OpenSea was the acquisition of “#3749,” an ape with golden fur, a captain’s hat, and red, laser eyes. It sold for 740 ETH or $2.7 million at current prices. (Interestingly it was bought by the official account of The Sandbox, the blockchain game we discussed earlier.)

OpenSea gives users the tools to filter and search projects by the delineations that matter most.

This might seem simple, but it makes a huge difference to buyers. Richard Chen articulated this position:

People under-appreciate how important search and discovery is for NFTs. Each NFT project (e.g. Meebits, Lost Poets) needs custom search filters by attributes, which has to be added manually by OpenSea on a project-by-project basis. This creates a huge defensible UX moat for OpenSea that’s hard for other platforms to replicate. For example, on Rarible I can’t even filter Meebits for skeletons that are wearing headphones; thus it doesn’t make sense to do my NFT shopping on one platform and then checkout on a different platform. By having a great NFT shopping user experience on OpenSea, users stay on the platform to do the actual NFT trade with OpenSea’s smart contract.

By treating each project as fundamentally unique, OpenSea has built a platform that truly caters to the buyer, simplifying the browsing experience so that it may capture the purchase.

In sum, OpenSea looks like an unusually crafty product that positioned itself perfectly to capture the effervescence of the last year. With a permissionless approach to creation, a huge number of assets on the platform, and a strong filtering system, it looks like a business encircled by subtle but significant moats.

Leadership and culture: Good winners

It is seemingly impossible to beguile Devin Finzer into gloating.

Despite serving as CEO of one of the most consequential unicorns in the world, despite his brainchild exerting a lordly dominance over its dominion, he is soft-spoken and mild-mannered.